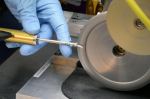

Providers such as Stryker Sustainability

Solutions have engineered special device-specific

machines that can safely dismantle devices,

such as this ultrasonic scalpel, for cleaning.

Solutions have engineered special device-specific

machines that can safely dismantle devices,

such as this ultrasonic scalpel, for cleaning.

Special Report: Single-use device reprocessing

January 14, 2013

by Nancy Ryerson, Staff Writer

There’s an easy way hospitals can save thousands of dollars a year while reducing their waste output and helping the planet: single-use device reprocessing. Devices labeled for single use are disinfected and otherwise made good as new at an offsite facility in an FDA-approved process. Reprocessed products are used at nearly 70 percent of hospitals in the U.S., including 16 of the country’s 17 Honor Roll hospitals as ranked by U.S. News & World Report. The FDA has found no higher risk of adverse events from reprocessed SUDs than from new ones. So why are some facilities still hesitant to get started?

“The first reaction is kind of a ‘yuck’ factor,” says Chris Lavanchy, engineering director at ECRI Institute. “Using something that was used on someone else, would I really want this used on me?”

According to single-use device reprocessors, and Lavanchy, the practice should be considered if it’s practical and makes financial sense. Thanks to extensive testing and FDA clearance before reprocessed devices can even hit the market, most experts say SUD reprocessing is safe, effective and saves a considerable amount of money. And it’s popular: the industry’s worth has grown from $20 million to a $400 million a year, even as some manufacturers remain adamantly against the practice citing concerns about safety as well as its impact to their bottom lines. The story of how SUD reprocessing grew from unregulated processes in hospital basements into a multi-million dollar industry is one that includes many safety reports and even a little high drama that continues to this day, as more and more hospitals incorporate it into their cost-saving and sustainability decisions.

A brief history of reprocessing

Many of the devices that are labeled for single use today started out as multiple-use. Some device manufacturers decided to transition to single-use only devices in the 1980s, partly because of the AIDs epidemic. In the mid-1990s, SUD reprocessing companies emerged in reaction to facilities’ interest in reusing certain devices, especially minimally invasive ones.

“Back around the mid-1990s, we were asked whether SUD reprocessing was a good idea,” says Lavanchy. “Hospitals were saying, things like saw blades, drill blades, they’re still sharp after use on a patient, it seems like such a waste to throw them away. At that time, hospitals reprocessed SUD items on their own, using their existing reprocessing protocols and technologies that they would use for capital equipment that’s intended for reuse, and trying to apply it to these single-use devices.”

At that time, the ECRI Institute did worry about the safety of SUD reprocessing, Lavanchy says, because there was not any oversight or assurance that the reprocessing was being handled in any consistent manner or being properly researched. In 1996, the institute published a monograph on the topic that described considerations and precautions facilities should take before starting SUD reprocessing.

A group of small, third-party SUD reprocessors founded the Association of Medical Device Reprocessors (AMDR) in 1997. In 2000, the Governmental Accountability Office put out a study on the safety of SUD reprocessing through third parties, and found no evidence to show that reprocessed devices were any less safe than the original devices. It did, however, call attention to the unregulated SUD reprocessing that was taking place within hospitals. Soon after, in 2002, the FDA determined that hospitals performing SUD reprocessing would need to register as manufacturers and be monitored as such, at which point third-party reprocessors gained further ground. In 2007, the FDA identified only one hospital reprocessing SUDs on-site. Today, ECRI does not recommend any hospital perform SUD reprocessing itself, Lavanchy says.

If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em

In 2009, Stryker acquired Ascent Healthcare Solutions, the leading reprocessing company at the time, and in 2011, Ethicon Endo-Surgery took on Sterilmed, the second largest reprocessing company. The AMDR is now made up of those two companies, which perform 95 percent of the reprocessing done in the United States.

“It’s been quite a ride,” says Chase Matson, manager of government relations at AMDR. “It’s not without its share of bumps of bruises because those companies that bought us up were the same companies fighting against us and what we were doing. But eventually they wised up and realized that we had a legit operation and that we were really fitting a need in the market.”

Before the acquisitions, friction between OEMs and reprocessors could be rather scandalous. Some manufacturers would even circulate pictures of unclean devices that they said had been ineffectively reprocessed.

“We called it the ‘dirty picture show,’” says AMDR president Dan Vukelich. “[Refuting the pictures] was a big part of my job for about 10 years, but now of course that’s water under the bridge. There’s a role for the original manufacturers and there’s a role for us. If they didn’t make great products, we wouldn’t have products to reprocess.”

Matson says the involvement of such large and trusted companies has given SUD reprocessing a further boost. Besides the two major reprocessors, other companies such as Hygia and Northeast Scientific have cropped up that cover specific device categories or only reprocess one device.

“We’re targeting niche opportunities, things that the larger players haven’t thought of or gotten around to yet,” says Phil Nalbone, VP of corporate development at Vascular Solutions, which reprocesses the Closure- Fast radiofrequency ablation catheter.

The art of reprocessing

Reprocessing a device is not as simple as wiping it off and sending it on its merry way, of course. First, a device must be cleared for reprocessing by the FDA. For most devices, the reprocessing company must prepare a separate 510(k) submission for the FDA, detailing how that device will be disassembled and cleaned, inspected, function tested and sterilized. The report must prove that the device is “substantially equivalent” to the original device. In total, more than 150 individual SUDs have been cleared for reprocessing.

The sterilization process differs from device to device, but most chemical usage involves primarily biodegradable detergents that are easily disposed of in the normal waste stream.

“Our target devices are non-invasive, so by nature reuse of a blood pressure cuff is less risky than reuse of a heart catheter,” says Scott Comas, CEO of Hygia, a reprocessing company that works with non-invasive devices. “Our processes are very patient-friendly in that we use mostly water, very few chemicals, so there are few residuals, carcinogens or allergens. In all of our operations, our byproduct is just run out into the sewer system.”

Benefits for price and planet

Reprocessed devices typically cost 50 percent less than new devices. Some hospitals can save as much as $600,000 annually, according to Brian White, president of Stryker Sustainability Solutions. Sterilmed reports that in 2011, the company reprocessed nearly 5 million devices, resulting in an estimated $83.5 million in customer savings. Inova Health Systems, for one, reports that it has saved $2.5 million since beginning a reprocessing program in 2009.

Reprocessing a pricey device, such as a harmonic scalpel, can save a hospital $2,000. But it’s not just the reprocessing of more expensive items that can save facilities money.

“If I’m a hospital executive or a materials director, I’m saying, $5 is not much savings, but hospitals use several hundred thousand of these non-invasive devices every year,” says Scott Comas, CEO of Hygia. “Every patient that goes to the hospital gets a blood pressure cuff.”

The waste-reduction benefits of reprocessing also factor into hospitals’ decisions. Sterilmed says its r eprocessing helps divert 2.5 million pounds of medical waste each year.

“The beauty of our devices is that even if it fails the function test and can’t be reprocessed, we still recycle the raw materials,” says Matson of AMDR.

Questions, concerns and continued controversy

For a hospital considering starting a reprocessing program or introducing more devices into its supply chain, Lavanchy of ECRI Institute recommends taking the type of device into consideration before making a decision.

“We’ve never found any evidence of a problem related to the use of an SUD, but there is a continuum, in terms of infection or safety risk,” he says. “Electrophysiology catheters, for example, go into the heart and are fairly complex, so I would put them on the more risky end of the scale. It’s something that should be considered after a careful riskbenefit analysis.”

Some hospitals choose to start with non-invasive devices and later warm up to the idea of expanding the program.

“Oftentimes, hospitals who are either hesitant to reprocess or are exploring reprocessing find our niche to be a great first step,” says Comas of Hygia. “We’ll get in and reprocess the non-invasive devices, then if they see that going well, they’ll include invasive devices down the line.” Some manufacturers are still not on board with SUD reprocessing. Medical device manufacturer Covidien, for example, continues to refute the safety of reprocessed devices. It explains on its website that single-use devices are not built for reprocessing and so may become less effective with reprocessing. It also points out that patients are not generally notified if a reprocessed SUD is being used during a procedure.

Others arguments against SUD reprocessing contend that it will substantially reduce revenues from OEMs and slow the development of new medical devices.

Today the U.S., tomorrow the world

Arguments aside, there is no denying that the SUD reprocessing industry has been expanding quickly. The market is expected to grow to over $4.4 billion by 2016, according to the Millennium Research Group.

[%%AD%]

AMDR President Vukelich says health care changes will likely have a positive impact on the industry. Reprocessed SUDs are reimbursed the same as original SUDs, and the increased use of group purchasing organizations may also boost the industry, as it will allow smaller facilities to get involved, MRG suggests. The industry also has plans to expand abroad. “The United States certainly isn’t the only country that wants to cut back on health care costs,” says Vukelich.

The list of FDA approvals for SUD reprocessing will likely continue to expand, as well.

“I would just say stay tuned, because I think we’re going to continue to show where reprocessing can help steer the ship,” says Matson. “We’re excited for what’s ahead.”

Names in boldface are Premium Listings.

Domestic

Adolfo Michel, United Endoscopy, CA

James Lantis, Seneca Scientific LLC, CO

DOTmed Certified

Arthur Morris, Medical Surplus Warehouse LLC, IN

“The first reaction is kind of a ‘yuck’ factor,” says Chris Lavanchy, engineering director at ECRI Institute. “Using something that was used on someone else, would I really want this used on me?”

According to single-use device reprocessors, and Lavanchy, the practice should be considered if it’s practical and makes financial sense. Thanks to extensive testing and FDA clearance before reprocessed devices can even hit the market, most experts say SUD reprocessing is safe, effective and saves a considerable amount of money. And it’s popular: the industry’s worth has grown from $20 million to a $400 million a year, even as some manufacturers remain adamantly against the practice citing concerns about safety as well as its impact to their bottom lines. The story of how SUD reprocessing grew from unregulated processes in hospital basements into a multi-million dollar industry is one that includes many safety reports and even a little high drama that continues to this day, as more and more hospitals incorporate it into their cost-saving and sustainability decisions.

A brief history of reprocessing

Many of the devices that are labeled for single use today started out as multiple-use. Some device manufacturers decided to transition to single-use only devices in the 1980s, partly because of the AIDs epidemic. In the mid-1990s, SUD reprocessing companies emerged in reaction to facilities’ interest in reusing certain devices, especially minimally invasive ones.

“Back around the mid-1990s, we were asked whether SUD reprocessing was a good idea,” says Lavanchy. “Hospitals were saying, things like saw blades, drill blades, they’re still sharp after use on a patient, it seems like such a waste to throw them away. At that time, hospitals reprocessed SUD items on their own, using their existing reprocessing protocols and technologies that they would use for capital equipment that’s intended for reuse, and trying to apply it to these single-use devices.”

At that time, the ECRI Institute did worry about the safety of SUD reprocessing, Lavanchy says, because there was not any oversight or assurance that the reprocessing was being handled in any consistent manner or being properly researched. In 1996, the institute published a monograph on the topic that described considerations and precautions facilities should take before starting SUD reprocessing.

A group of small, third-party SUD reprocessors founded the Association of Medical Device Reprocessors (AMDR) in 1997. In 2000, the Governmental Accountability Office put out a study on the safety of SUD reprocessing through third parties, and found no evidence to show that reprocessed devices were any less safe than the original devices. It did, however, call attention to the unregulated SUD reprocessing that was taking place within hospitals. Soon after, in 2002, the FDA determined that hospitals performing SUD reprocessing would need to register as manufacturers and be monitored as such, at which point third-party reprocessors gained further ground. In 2007, the FDA identified only one hospital reprocessing SUDs on-site. Today, ECRI does not recommend any hospital perform SUD reprocessing itself, Lavanchy says.

If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em

In 2009, Stryker acquired Ascent Healthcare Solutions, the leading reprocessing company at the time, and in 2011, Ethicon Endo-Surgery took on Sterilmed, the second largest reprocessing company. The AMDR is now made up of those two companies, which perform 95 percent of the reprocessing done in the United States.

“It’s been quite a ride,” says Chase Matson, manager of government relations at AMDR. “It’s not without its share of bumps of bruises because those companies that bought us up were the same companies fighting against us and what we were doing. But eventually they wised up and realized that we had a legit operation and that we were really fitting a need in the market.”

Before the acquisitions, friction between OEMs and reprocessors could be rather scandalous. Some manufacturers would even circulate pictures of unclean devices that they said had been ineffectively reprocessed.

“We called it the ‘dirty picture show,’” says AMDR president Dan Vukelich. “[Refuting the pictures] was a big part of my job for about 10 years, but now of course that’s water under the bridge. There’s a role for the original manufacturers and there’s a role for us. If they didn’t make great products, we wouldn’t have products to reprocess.”

Matson says the involvement of such large and trusted companies has given SUD reprocessing a further boost. Besides the two major reprocessors, other companies such as Hygia and Northeast Scientific have cropped up that cover specific device categories or only reprocess one device.

“We’re targeting niche opportunities, things that the larger players haven’t thought of or gotten around to yet,” says Phil Nalbone, VP of corporate development at Vascular Solutions, which reprocesses the Closure- Fast radiofrequency ablation catheter.

The art of reprocessing

Reprocessing a device is not as simple as wiping it off and sending it on its merry way, of course. First, a device must be cleared for reprocessing by the FDA. For most devices, the reprocessing company must prepare a separate 510(k) submission for the FDA, detailing how that device will be disassembled and cleaned, inspected, function tested and sterilized. The report must prove that the device is “substantially equivalent” to the original device. In total, more than 150 individual SUDs have been cleared for reprocessing.

The sterilization process differs from device to device, but most chemical usage involves primarily biodegradable detergents that are easily disposed of in the normal waste stream.

“Our target devices are non-invasive, so by nature reuse of a blood pressure cuff is less risky than reuse of a heart catheter,” says Scott Comas, CEO of Hygia, a reprocessing company that works with non-invasive devices. “Our processes are very patient-friendly in that we use mostly water, very few chemicals, so there are few residuals, carcinogens or allergens. In all of our operations, our byproduct is just run out into the sewer system.”

Benefits for price and planet

Reprocessed devices typically cost 50 percent less than new devices. Some hospitals can save as much as $600,000 annually, according to Brian White, president of Stryker Sustainability Solutions. Sterilmed reports that in 2011, the company reprocessed nearly 5 million devices, resulting in an estimated $83.5 million in customer savings. Inova Health Systems, for one, reports that it has saved $2.5 million since beginning a reprocessing program in 2009.

Reprocessing a pricey device, such as a harmonic scalpel, can save a hospital $2,000. But it’s not just the reprocessing of more expensive items that can save facilities money.

“If I’m a hospital executive or a materials director, I’m saying, $5 is not much savings, but hospitals use several hundred thousand of these non-invasive devices every year,” says Scott Comas, CEO of Hygia. “Every patient that goes to the hospital gets a blood pressure cuff.”

The waste-reduction benefits of reprocessing also factor into hospitals’ decisions. Sterilmed says its r eprocessing helps divert 2.5 million pounds of medical waste each year.

“The beauty of our devices is that even if it fails the function test and can’t be reprocessed, we still recycle the raw materials,” says Matson of AMDR.

Questions, concerns and continued controversy

For a hospital considering starting a reprocessing program or introducing more devices into its supply chain, Lavanchy of ECRI Institute recommends taking the type of device into consideration before making a decision.

“We’ve never found any evidence of a problem related to the use of an SUD, but there is a continuum, in terms of infection or safety risk,” he says. “Electrophysiology catheters, for example, go into the heart and are fairly complex, so I would put them on the more risky end of the scale. It’s something that should be considered after a careful riskbenefit analysis.”

Some hospitals choose to start with non-invasive devices and later warm up to the idea of expanding the program.

“Oftentimes, hospitals who are either hesitant to reprocess or are exploring reprocessing find our niche to be a great first step,” says Comas of Hygia. “We’ll get in and reprocess the non-invasive devices, then if they see that going well, they’ll include invasive devices down the line.” Some manufacturers are still not on board with SUD reprocessing. Medical device manufacturer Covidien, for example, continues to refute the safety of reprocessed devices. It explains on its website that single-use devices are not built for reprocessing and so may become less effective with reprocessing. It also points out that patients are not generally notified if a reprocessed SUD is being used during a procedure.

Others arguments against SUD reprocessing contend that it will substantially reduce revenues from OEMs and slow the development of new medical devices.

Today the U.S., tomorrow the world

Arguments aside, there is no denying that the SUD reprocessing industry has been expanding quickly. The market is expected to grow to over $4.4 billion by 2016, according to the Millennium Research Group.

[%%AD%]

AMDR President Vukelich says health care changes will likely have a positive impact on the industry. Reprocessed SUDs are reimbursed the same as original SUDs, and the increased use of group purchasing organizations may also boost the industry, as it will allow smaller facilities to get involved, MRG suggests. The industry also has plans to expand abroad. “The United States certainly isn’t the only country that wants to cut back on health care costs,” says Vukelich.

The list of FDA approvals for SUD reprocessing will likely continue to expand, as well.

“I would just say stay tuned, because I think we’re going to continue to show where reprocessing can help steer the ship,” says Matson. “We’re excited for what’s ahead.”

DOTmed Registered DMBN - January 2013 Reprocessing Companies

Names in boldface are Premium Listings.

Domestic

Adolfo Michel, United Endoscopy, CA

James Lantis, Seneca Scientific LLC, CO

DOTmed Certified

Arthur Morris, Medical Surplus Warehouse LLC, IN