Tackling the PPE challenge for better healthcare safety, provider satisfaction

August 11, 2020

By Deepak Prakash

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to teach hard lessons on many fronts, with regard to crisis preparedness, testing, global supply chains, personal protective equipment (PPE), social distancing and public health and economic policies. This article focuses on one of these challenges, PPE, and discusses how issues stemming from the pandemic promise to drive better PPE design and supply chain reliability.

PPE design and user experience

Essential healthcare workers should not have to wear PPE that is so uncomfortable that it becomes an added stressor on the job or a threat to their own health. Case in point: The traditional half-mask N95 filtering facepiece respirator (FFR) is designed to fit tightly against the wearer’s face. There must be an airtight seal around the edge of the device for it to function properly. However, this design, while effective, can cause considerable discomfort and even injury for some healthcare providers, especially if they have to wear the same device for many hours at a time. This has been the case during the COVID-19 crisis, with its widespread PPE shortages.

The Association of Nurses Specialized in Wound, Ostomy and Continence Canada (NSWOCC) has published suggested solutions for coping with the problem in its “Prevention and Management of Skin Damage Related to PPE: Update 2020.” “Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, skin conditions mainly related to the use of PPE and frequent skin cleansing have emerged including pressure injuries, contact dermatitis, itching, and hives related to pressure,” according to the update. “Despite numerous personal and media reports by healthcare professionals of PPE-related skin injuries (pressure injuries, friction injuries, contact dermatitis and moisture associated skin damage), there exists limited published evidence to support the prevention of these wounds.”

Among other recommendations, the NSWOCC offers guidance for how clinicians can apply creams, dressings and foams to protect sensitive facial skin from respirator pressure. But it emphasized that such measures should only be taken if they are approved by the provider’s healthcare institution and do not impair PPE performance.

When clinicians have to apply first aid to themselves in order to wear their PPE, we must ask the question: What can the healthcare supply chain do differently to remedy this unacceptable state of affairs? Part of the answer is for device developers, material suppliers, clinicians, supply chain leaders and other healthcare ecosystem constituents to collaborate for more comfortable PPE solutions.

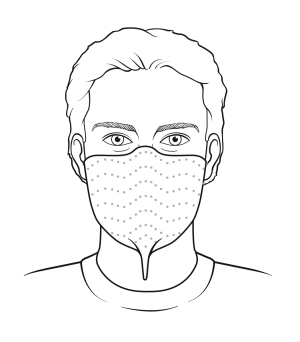

Can an N95 FFR be made of a more breathable material to help keep the wearer cooler and more comfortable? Is there a design that can create an airtight seal without applying pressure to the face? Can respirators be made without the metal nose clip so that patients and providers can wear them for MRI procedures? The answer is yes on all counts. This summer, a different type of N95 respirator, approved by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), is expected to ship to the healthcare industry. This half-mask FFR, made of a breathable barrier material, adheres directly to the face with a skin-friendly adhesive.

This is just one example of how a different approach to PPE design can potentially make a big difference for the user experience. If the industry can keep focusing resources on the PPE issue, there could be other innovations — new types of gloves, gowns, coveralls, face shields and masks. Advances may offer incremental improvements or represent full reinvention. Any improvement on the status quo is progress.

Healthcare institutions that prioritize provider comfort and user experience in their PPE procurement are likely to have greater satisfaction among their clinical and essential team members. Moreover, when providers are not distracted by their own discomfort, they are better able to provide high quality patient-centered care.

PPE supply chain stability

Having PPE that is comfortable, of course, is a secondary consideration when there are concerns about having any PPE at all. The U.S. healthcare industry’s PPE shortages have been well publicized, but we may not yet know its full impact on healthcare workers. Some have paid with their lives. Others suffer from stress, which can cause a cascade of mental and physical health problems. It also can impact their ability to function at their best and be satisfied with their work environment.

The journal Brain, Behavior, and Immunity has published results of a study of Iranian healthcare workers’ health and job satisfaction at the peak of Iran’s COVID-19 outbreak. “Our research uncovered unique risk factors. … PPE access predicted better physical health and job satisfaction and less distress, demonstrating its importance beyond physical protection,” the authors said.

The Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC) is encouraging its members to write to their elected officials, asking them to support broader use of the U.S. Defense Production Act to acquire PPE. “Without proper PPE, we are asking healthcare professionals to care for patients at the risk of their own health and the health of their families,” said APIC’s letter to Congress members.

While much more needs to be done, there has been progress. As of this writing in June 2020, Project 95, a national nonprofit PPE clearinghouse, reported there was an immediate need for more than 2.5 million PPE units across the United States. This demand is much lower than it was in March and April, when Connecticut alone needed over 2 million PPE units. But it still is a problem to have any shortages of something so critical.

Healthcare institutions, distributors, group purchasing organizations, PPE manufacturers and materials suppliers are all taking a fresh view of their supply chains. They are asking the important questions, including:

• How robust is my PPE supply chain? Does my organization have secondary PPE sources? Do my suppliers have secondary sources?

• What are the lead times for different types of PPE? What are the lead times for raw materials required to make PPE?

• Do my PPE suppliers have U.S.-based manufacturing capacity in case of global supply chain disruptions?

• Do new PPE suppliers hold all of the necessary regulatory approvals and certifications? Have they successfully completed product testing?

• What is the security of my PPE supply? What assurances and controls do PPE suppliers have in place to protect against fraud, such as counterfeit and poor-quality PPE?

• Can my suppliers provide documentation to prove N95 respirators are certified by NIOSH?

• Have the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued reports of PPE fraud or quality problems affecting my supply chain?

• Do my PPE suppliers and their suppliers comply with Current Good Manufacturing Practices? Are their facilities registered with the FDA? Are they certified under standard 13485 of the International Organization for Standardization? Are they certified under the Medical Device Single Audit Program?

In conclusion, the healthcare industry has an opportunity to apply lessons learned from the COVID-19 crisis to improve both PPE user experience and supply stability. The rewards for doing so include greater safety and overall satisfaction for healthcare providers and the patients they serve.

About the Author: Deepak Prakash is senior director, global marketing, Avery Dennison Medical. He can be reached at deepak.prakash@averydennison.com.

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to teach hard lessons on many fronts, with regard to crisis preparedness, testing, global supply chains, personal protective equipment (PPE), social distancing and public health and economic policies. This article focuses on one of these challenges, PPE, and discusses how issues stemming from the pandemic promise to drive better PPE design and supply chain reliability.

PPE design and user experience

Essential healthcare workers should not have to wear PPE that is so uncomfortable that it becomes an added stressor on the job or a threat to their own health. Case in point: The traditional half-mask N95 filtering facepiece respirator (FFR) is designed to fit tightly against the wearer’s face. There must be an airtight seal around the edge of the device for it to function properly. However, this design, while effective, can cause considerable discomfort and even injury for some healthcare providers, especially if they have to wear the same device for many hours at a time. This has been the case during the COVID-19 crisis, with its widespread PPE shortages.

The Association of Nurses Specialized in Wound, Ostomy and Continence Canada (NSWOCC) has published suggested solutions for coping with the problem in its “Prevention and Management of Skin Damage Related to PPE: Update 2020.” “Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, skin conditions mainly related to the use of PPE and frequent skin cleansing have emerged including pressure injuries, contact dermatitis, itching, and hives related to pressure,” according to the update. “Despite numerous personal and media reports by healthcare professionals of PPE-related skin injuries (pressure injuries, friction injuries, contact dermatitis and moisture associated skin damage), there exists limited published evidence to support the prevention of these wounds.”

Among other recommendations, the NSWOCC offers guidance for how clinicians can apply creams, dressings and foams to protect sensitive facial skin from respirator pressure. But it emphasized that such measures should only be taken if they are approved by the provider’s healthcare institution and do not impair PPE performance.

When clinicians have to apply first aid to themselves in order to wear their PPE, we must ask the question: What can the healthcare supply chain do differently to remedy this unacceptable state of affairs? Part of the answer is for device developers, material suppliers, clinicians, supply chain leaders and other healthcare ecosystem constituents to collaborate for more comfortable PPE solutions.

Can an N95 FFR be made of a more breathable material to help keep the wearer cooler and more comfortable? Is there a design that can create an airtight seal without applying pressure to the face? Can respirators be made without the metal nose clip so that patients and providers can wear them for MRI procedures? The answer is yes on all counts. This summer, a different type of N95 respirator, approved by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), is expected to ship to the healthcare industry. This half-mask FFR, made of a breathable barrier material, adheres directly to the face with a skin-friendly adhesive.

This is just one example of how a different approach to PPE design can potentially make a big difference for the user experience. If the industry can keep focusing resources on the PPE issue, there could be other innovations — new types of gloves, gowns, coveralls, face shields and masks. Advances may offer incremental improvements or represent full reinvention. Any improvement on the status quo is progress.

Healthcare institutions that prioritize provider comfort and user experience in their PPE procurement are likely to have greater satisfaction among their clinical and essential team members. Moreover, when providers are not distracted by their own discomfort, they are better able to provide high quality patient-centered care.

PPE supply chain stability

Having PPE that is comfortable, of course, is a secondary consideration when there are concerns about having any PPE at all. The U.S. healthcare industry’s PPE shortages have been well publicized, but we may not yet know its full impact on healthcare workers. Some have paid with their lives. Others suffer from stress, which can cause a cascade of mental and physical health problems. It also can impact their ability to function at their best and be satisfied with their work environment.

The journal Brain, Behavior, and Immunity has published results of a study of Iranian healthcare workers’ health and job satisfaction at the peak of Iran’s COVID-19 outbreak. “Our research uncovered unique risk factors. … PPE access predicted better physical health and job satisfaction and less distress, demonstrating its importance beyond physical protection,” the authors said.

The Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC) is encouraging its members to write to their elected officials, asking them to support broader use of the U.S. Defense Production Act to acquire PPE. “Without proper PPE, we are asking healthcare professionals to care for patients at the risk of their own health and the health of their families,” said APIC’s letter to Congress members.

This N95 respirator adheres to the face with a thin strip of skin-friendly adhesive. This is an example of an alternative N95 respirator. Image courtesy of Avery Dennison Medical.

Healthcare institutions, distributors, group purchasing organizations, PPE manufacturers and materials suppliers are all taking a fresh view of their supply chains. They are asking the important questions, including:

• How robust is my PPE supply chain? Does my organization have secondary PPE sources? Do my suppliers have secondary sources?

• What are the lead times for different types of PPE? What are the lead times for raw materials required to make PPE?

• Do my PPE suppliers have U.S.-based manufacturing capacity in case of global supply chain disruptions?

• Do new PPE suppliers hold all of the necessary regulatory approvals and certifications? Have they successfully completed product testing?

• What is the security of my PPE supply? What assurances and controls do PPE suppliers have in place to protect against fraud, such as counterfeit and poor-quality PPE?

• Can my suppliers provide documentation to prove N95 respirators are certified by NIOSH?

• Have the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued reports of PPE fraud or quality problems affecting my supply chain?

• Do my PPE suppliers and their suppliers comply with Current Good Manufacturing Practices? Are their facilities registered with the FDA? Are they certified under standard 13485 of the International Organization for Standardization? Are they certified under the Medical Device Single Audit Program?

In conclusion, the healthcare industry has an opportunity to apply lessons learned from the COVID-19 crisis to improve both PPE user experience and supply stability. The rewards for doing so include greater safety and overall satisfaction for healthcare providers and the patients they serve.

About the Author: Deepak Prakash is senior director, global marketing, Avery Dennison Medical. He can be reached at deepak.prakash@averydennison.com.