The SCCA Proton Therapy Center celebrates Ryder, their 3,000th patient, completing cancer treatment in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. ©2020 SCCA Proton Therapy Center. Photo by Caroline Catlin

Proton therapy providers navigating COVID-19 cautiously

October 05, 2020

by John R. Fischer, Senior Reporter

Many medical procedures and exams can be safely delayed during the COVID-19 pandemic, but prolonged delays in cancer treatment can lead to disease advancement and worsened outcomes. This is especially true for patients receiving treatment for more aggressive and complex tumors — the types of tumors that proton therapy is uniquely effective against.

Proton International at UAB, the first and only proton therapy center in Alabama, has a plan ready should the day come when a cancer patient who has tested positive for the virus enters its doors.

"We would dress in full PPE," Lindsay Pruett, the center administrator, told HCB News. " We would keep only the staff necessary for that patient's care in the building, which includes two therapists, one physician and one nurse. We would have all other staff and patients leave for the day before the positive patient arrives. We would bring the patient in through a secondary entrance, not through the lobby, and bring them directly to the treatment room. We would deliver their treatment, walk them out through the same entrance, and then disinfect all surfaces as prescribed."

Like Proton International at UAB, proton therapy centers across the U.S. have implemented new guidelines around sanitizing and disinfection, as well as PPE and social distancing, as patient volumes begin to resume at normal levels following drops in the last few months in the number entering their facilities. Like other types of providers, the pandemic has caused the proton therapy facilities to reevaluate their day-to-day practices in how they deliver care to patients, both now and after the virus has subsided.

Preparation and planning are not only a benefit to COVID-19-positive cancer patients, but they also send the message to non-COVID patients that they can be confident in the safety of the care they’re receiving.

Resuming patient visits

Cancer screenings dropped by about 90% during the first three months of the pandemic compared to where they stood a year earlier, according to The American Cancer Society. Overall, cancer care was down 35% to 40% nationally, with the reduction in screening leading to fewer referrals, which for proton therapy centers meant fewer new patients arriving for treatment.

“By June, because there were so many months that had gone by with patients not getting their mammograms, colonoscopies, PSAs or surgical biopsies, there were significantly fewer new diagnoses coming into the building,” said Dr. Charles Simone, chief medical officer of the New York Proton Center. “Plus, a lot of patients were still hesitant to come in for their care. So we did see a significant downturn in our patient volume in June and July before rebounding, really as all centers in New York did.”

While the New York Proton Center saw patient volume pick back up in August, out-of-state and international patients in many places still face barriers from travel lockdowns. The SCCA Proton Therapy Center in Seattle, for instance, treats a number of patients from British Columbia, Canada but border closures between the U.S. and Canada meant these patients couldn’t get the care they needed, (there are no proton therapy centers in Canada).

"It stalled several patients coming from there," said Lindsay Knapp, associate administrator for the SCCA Proton Therapy Center. "While there haven’t necessarily been travel restrictions from places like Idaho, Oregon, Montana, and Washington State, there has been quite a bit of anxiety, particularly in the earlier stages of the pandemic where patients would personally opt not to travel for treatment."

Another challenge was the shutdown of lodging companies. As popular venues that offer affordable or no-cost stays to cancer patients, such as Hope Lodges and Ronald McDonald House closed their doors, care providers had to network and forge new partnerships.

“NAPT has provided resources to proton centers, such as Airbnb programs through the Cancer Support Community,” said Jennifer Maggiore, executive director for the National Association for Proton Therapy. “We’ve educated our members with frequent community town hall meetings regarding the impact of COVID-19 on cancer treatments. Proton therapy facilities are also providing navigation services to ensure patients have the opportunity to travel throughout the pandemic for necessary treatments while receiving supportive resources.”

A new way of doing things

Proton facilities like Roberts Proton Therapy Center at Penn Medicine are finding ways to reduce foot traffic with the use of telehealth. In addition to cutting down on the risk of spreading COVID-19, telehealth visits prior to and in-between planning and treatment sessions provide a less stressful experience for patients, who can interface with their care team from the comfort of home.

“We’re now a hybrid model,” said Dr. Michelle Alonso-Basanta, vice chair of the clinical division for the department of radiation oncology at Penn Medicine. “We did go to telehealth early on in the process but still had in-person visits, especially for very symptomatic patients, both new and returning patients. Then we switched to hybrid. Most of our new patients are in-person, although we are still providing telehealth for both new and returning patients. The use of telehealth allows us to see our new patients in a timely manner, with our preference for video visits but also including telephone visits for those without video capacity.”

Proton therapy providers have also implemented new regulations requiring staff to wear masks at all times and gloves when handling patients, practice social distancing, and abide by hand sanitizing policies. Some have shut down their lobbies, requiring patients to instead wait in their vehicles and go through a screening station in front of their facilities before entering. Proton International at UAB directed any staff members that could work from home to do so.

"We have tried to limit our exposure risks outside of work and use PPE when appropriate, as losing even one or two staff members to infection or quarantine would significantly hamper operations," said Dr. J.W. Snider, associate professor of radiation oncology at UAB and medical director of the proton center. "Our staff has tried to be conscientious in their personal lives as well to try to protect themselves, their patients, and their coworkers from infection."

Resources and guidelines to support healthcare providers have been issued by health departments and government agencies like the CDC. In addition, proton centers in places that experienced the brunt of the pandemic early on, (New York and Seattle, for instance) have also passed along lessons learned to their peers in other regions via virtual meetings. Tom Wang, president of ProCure Proton Center in New Jersey, says the best guidance he got was a decision tree issued by the state’s Department of Health.

“It strictly stated that if you had the clinician — doctor, nurse or therapist on our end — wearing a surgical mask, and also the patient wearing a surgical mask, even if one individual is considered to be ultimately COVID-19 positive, that would be considered a low-risk contact,” he said. “And if there were other individuals that came into contact with that person who tested positive, they would be considered low-risk contacts and would not need to be quarantined. We took that strongly to heart and tried to enforce that every step of the way to ensure the utmost confidence in our patient safety protocol.”

In some cases, less urgent treatments could be delayed in order to reduce the risk of spreading COVID-19 while dedicating resources to the patients who required more immediate care. For SCCA in Seattle, this meant pushing back certain low-risk prostate cancer patients during the early outbreak in Washington.

"They were deferred from starting treatment during March and April. We resumed treatment for those types of patients in May,” said Knapp. “A lot of local healthcare providers were working to minimize elective and non-urgent procedures in order to limit the number of people coming in and out of buildings, and to keep their staff safe and ready to go in the event that the Seattle area had a surge of COVID-19 cases and our specialists were needed to treat patients with urgent needs at other facilities.”

Relooking at practices and disparities in care

The COVID-19 pandemic has not only created new hurdles for providing proton therapy, it has also shed light on challenges that have existed under the radar for a long time. This is especially true with regard to ensuring access for the patients who need it most, and improving awareness and education surrounding proton treatment and cancer screening in general.

“Patients that are underinsured may have limited access to advanced cancer treatments. Medicaid does not always cover some treatments covered by commercial insurances or even Medicare,” said Maggiore. “We need to support the development of proton therapy centers in other regions. It’s very difficult for people to leave their home and job for treatment not offered near them. If this treatment and other advanced treatments are available regionally, that will help patients access this treatment.”

These issues exponentially impact minority patients such as African-Americans, who have the highest death rate in the U.S. from most cancers and can potentially be subject to referral bias.

“To have a fundamental change beyond just our center and our community, we need all relevant stakeholders — lawmakers, providers, insurers — to have a clear drive to improve outcomes for all patients, not based on the color of their skin or the income of the patients,” said Dr. Charles Simone of The New York Proton Center.

Prior to the pandemic, Simone and his colleagues addressed these challenges in regular educational talks with the community about cancer prevention and screening. He hopes to resume them once it is safe to do so.

The SCCA Proton Therapy Center has an appeals coordinator who helps persuade insurance companies to cover certain patients. It also recently worked with the Washington State Healthcare Authority to show the benefits of proton therapy and expand coverage in Washington state.

"Out of that we were able to get an expansion in proton therapy coverage that improved access for the Medicaid populations here in Washington state," said Knapp. "Continuing to improve the evidence available and working with insurance companies to be able to get broader coverage is one of the key elements to making proton therapy widely accessible to all people.”

Alonso-Basanta with Penn Medicine sees a silver lining of the COVID-19 pandemic. For all the trouble and challenges it created, it has also provided a reminder that protocols and ways of doing things can always be improved.

“It forced us to reexamine our processes and staff to look at efficiencies,” she said. “Thankfully, we prepared very early in advance to be able to come across a number of different situations and bring care to our patients regardless of COVID, with many more eyes on every process that we were doing. I think every proton center probably did the exact same thing. It’s reviewing overall the way we used to do things and asking if it was the most efficient way to do it to allow patients to get treatment. The benefit was re-looking at our processes as a whole.”

Proton International at UAB, the first and only proton therapy center in Alabama, has a plan ready should the day come when a cancer patient who has tested positive for the virus enters its doors.

"We would dress in full PPE," Lindsay Pruett, the center administrator, told HCB News. " We would keep only the staff necessary for that patient's care in the building, which includes two therapists, one physician and one nurse. We would have all other staff and patients leave for the day before the positive patient arrives. We would bring the patient in through a secondary entrance, not through the lobby, and bring them directly to the treatment room. We would deliver their treatment, walk them out through the same entrance, and then disinfect all surfaces as prescribed."

Proton therapy providers wearing face masks and practicing social distancing. Photo courtesy of the New York Proton Center.

Preparation and planning are not only a benefit to COVID-19-positive cancer patients, but they also send the message to non-COVID patients that they can be confident in the safety of the care they’re receiving.

Resuming patient visits

Cancer screenings dropped by about 90% during the first three months of the pandemic compared to where they stood a year earlier, according to The American Cancer Society. Overall, cancer care was down 35% to 40% nationally, with the reduction in screening leading to fewer referrals, which for proton therapy centers meant fewer new patients arriving for treatment.

“By June, because there were so many months that had gone by with patients not getting their mammograms, colonoscopies, PSAs or surgical biopsies, there were significantly fewer new diagnoses coming into the building,” said Dr. Charles Simone, chief medical officer of the New York Proton Center. “Plus, a lot of patients were still hesitant to come in for their care. So we did see a significant downturn in our patient volume in June and July before rebounding, really as all centers in New York did.”

While the New York Proton Center saw patient volume pick back up in August, out-of-state and international patients in many places still face barriers from travel lockdowns. The SCCA Proton Therapy Center in Seattle, for instance, treats a number of patients from British Columbia, Canada but border closures between the U.S. and Canada meant these patients couldn’t get the care they needed, (there are no proton therapy centers in Canada).

"It stalled several patients coming from there," said Lindsay Knapp, associate administrator for the SCCA Proton Therapy Center. "While there haven’t necessarily been travel restrictions from places like Idaho, Oregon, Montana, and Washington State, there has been quite a bit of anxiety, particularly in the earlier stages of the pandemic where patients would personally opt not to travel for treatment."

Another challenge was the shutdown of lodging companies. As popular venues that offer affordable or no-cost stays to cancer patients, such as Hope Lodges and Ronald McDonald House closed their doors, care providers had to network and forge new partnerships.

“NAPT has provided resources to proton centers, such as Airbnb programs through the Cancer Support Community,” said Jennifer Maggiore, executive director for the National Association for Proton Therapy. “We’ve educated our members with frequent community town hall meetings regarding the impact of COVID-19 on cancer treatments. Proton therapy facilities are also providing navigation services to ensure patients have the opportunity to travel throughout the pandemic for necessary treatments while receiving supportive resources.”

A new way of doing things

Proton facilities like Roberts Proton Therapy Center at Penn Medicine are finding ways to reduce foot traffic with the use of telehealth. In addition to cutting down on the risk of spreading COVID-19, telehealth visits prior to and in-between planning and treatment sessions provide a less stressful experience for patients, who can interface with their care team from the comfort of home.

“We’re now a hybrid model,” said Dr. Michelle Alonso-Basanta, vice chair of the clinical division for the department of radiation oncology at Penn Medicine. “We did go to telehealth early on in the process but still had in-person visits, especially for very symptomatic patients, both new and returning patients. Then we switched to hybrid. Most of our new patients are in-person, although we are still providing telehealth for both new and returning patients. The use of telehealth allows us to see our new patients in a timely manner, with our preference for video visits but also including telephone visits for those without video capacity.”

Proton therapy providers have also implemented new regulations requiring staff to wear masks at all times and gloves when handling patients, practice social distancing, and abide by hand sanitizing policies. Some have shut down their lobbies, requiring patients to instead wait in their vehicles and go through a screening station in front of their facilities before entering. Proton International at UAB directed any staff members that could work from home to do so.

"We have tried to limit our exposure risks outside of work and use PPE when appropriate, as losing even one or two staff members to infection or quarantine would significantly hamper operations," said Dr. J.W. Snider, associate professor of radiation oncology at UAB and medical director of the proton center. "Our staff has tried to be conscientious in their personal lives as well to try to protect themselves, their patients, and their coworkers from infection."

Resources and guidelines to support healthcare providers have been issued by health departments and government agencies like the CDC. In addition, proton centers in places that experienced the brunt of the pandemic early on, (New York and Seattle, for instance) have also passed along lessons learned to their peers in other regions via virtual meetings. Tom Wang, president of ProCure Proton Center in New Jersey, says the best guidance he got was a decision tree issued by the state’s Department of Health.

“It strictly stated that if you had the clinician — doctor, nurse or therapist on our end — wearing a surgical mask, and also the patient wearing a surgical mask, even if one individual is considered to be ultimately COVID-19 positive, that would be considered a low-risk contact,” he said. “And if there were other individuals that came into contact with that person who tested positive, they would be considered low-risk contacts and would not need to be quarantined. We took that strongly to heart and tried to enforce that every step of the way to ensure the utmost confidence in our patient safety protocol.”

In some cases, less urgent treatments could be delayed in order to reduce the risk of spreading COVID-19 while dedicating resources to the patients who required more immediate care. For SCCA in Seattle, this meant pushing back certain low-risk prostate cancer patients during the early outbreak in Washington.

"They were deferred from starting treatment during March and April. We resumed treatment for those types of patients in May,” said Knapp. “A lot of local healthcare providers were working to minimize elective and non-urgent procedures in order to limit the number of people coming in and out of buildings, and to keep their staff safe and ready to go in the event that the Seattle area had a surge of COVID-19 cases and our specialists were needed to treat patients with urgent needs at other facilities.”

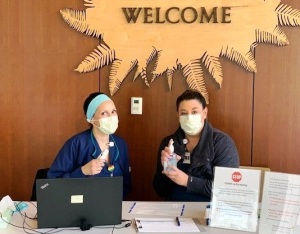

A nursing station at the SCCA Proton Therapy Center checks incoming patients for COVID-19 symptoms and provides hand sanitizer.

The COVID-19 pandemic has not only created new hurdles for providing proton therapy, it has also shed light on challenges that have existed under the radar for a long time. This is especially true with regard to ensuring access for the patients who need it most, and improving awareness and education surrounding proton treatment and cancer screening in general.

“Patients that are underinsured may have limited access to advanced cancer treatments. Medicaid does not always cover some treatments covered by commercial insurances or even Medicare,” said Maggiore. “We need to support the development of proton therapy centers in other regions. It’s very difficult for people to leave their home and job for treatment not offered near them. If this treatment and other advanced treatments are available regionally, that will help patients access this treatment.”

These issues exponentially impact minority patients such as African-Americans, who have the highest death rate in the U.S. from most cancers and can potentially be subject to referral bias.

“To have a fundamental change beyond just our center and our community, we need all relevant stakeholders — lawmakers, providers, insurers — to have a clear drive to improve outcomes for all patients, not based on the color of their skin or the income of the patients,” said Dr. Charles Simone of The New York Proton Center.

Prior to the pandemic, Simone and his colleagues addressed these challenges in regular educational talks with the community about cancer prevention and screening. He hopes to resume them once it is safe to do so.

The SCCA Proton Therapy Center has an appeals coordinator who helps persuade insurance companies to cover certain patients. It also recently worked with the Washington State Healthcare Authority to show the benefits of proton therapy and expand coverage in Washington state.

"Out of that we were able to get an expansion in proton therapy coverage that improved access for the Medicaid populations here in Washington state," said Knapp. "Continuing to improve the evidence available and working with insurance companies to be able to get broader coverage is one of the key elements to making proton therapy widely accessible to all people.”

Alonso-Basanta with Penn Medicine sees a silver lining of the COVID-19 pandemic. For all the trouble and challenges it created, it has also provided a reminder that protocols and ways of doing things can always be improved.

“It forced us to reexamine our processes and staff to look at efficiencies,” she said. “Thankfully, we prepared very early in advance to be able to come across a number of different situations and bring care to our patients regardless of COVID, with many more eyes on every process that we were doing. I think every proton center probably did the exact same thing. It’s reviewing overall the way we used to do things and asking if it was the most efficient way to do it to allow patients to get treatment. The benefit was re-looking at our processes as a whole.”