by

Brendon Nafziger, DOTmed News Associate Editor | August 02, 2012

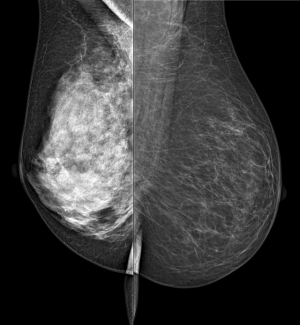

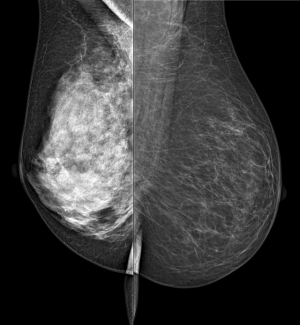

The left breast,

white in the center,

shows high density

(Credit: AAPM)

A new mammography technique could give automatic breast density measurements, possibly enabling doctors to better gauge their patients' cancer risk and steer them toward MRI scans or other, more sensitive modalities, according to a new study.

Called spectral mammography, the technology calculates energy from X-rays hitting a detector to quantify a woman's volumetric breast density, researchers reported Thursday at the American Association of Physicists in Medicine's annual meeting in Charlotte, N.C.

"Spectral mammography could become a standard of care for screening mammograms and could identify high-risk women who could benefit from more sensitive screening exams," Huanjun Ding, a researcher on the study, told reporters on a call ahead of the conference.

Ad Statistics

Times Displayed: 797

Times Visited: 5 Keep biomedical devices ready to go, so care teams can be ready to care for patients. GE HealthCare’s ReadySee™ helps overcome frustrations due to lack of network and device visibility, manual troubleshooting, and downtime.

Mammographically dense breasts have less fat and more glandular and connective tissue, which appears white, like cancer, on a mammogram, sometimes making it harder for doctors to spot lesions.

Since the 1970s, scientists have known that higher breast density increases a woman's risk for cancer, Ding said. Partly, it's that radiologists are more likely to miss cancers on the mammogram, but it's also possible that the physical makeup of the breast makes it more prone to develop malignancies.

Are You Dense, an advocacy group, estimates 40 percent of women have dense breasts.

Photon counting

To carry out the study, the researchers, all affiliated with the University of California at Irvine, used a special kind of mammography unit that's capable of "photon counting," a process that lets the detector record the energy from the X-ray photons as they hit it, according to Sabee Molloi, a study co-author and a professor at UC Irvine. With this "spectrum" energy information, the researchers can quantify the breast tissue's mammographic density.

"(It) mirrors density based on the physics of interaction between X-rays and tissue," Ding said. "It's fully automatic, and doesn't depend on the experience of the radiologist."

In the abstract presented at the show, the researchers said they scanned four breast phantoms of varying levels of thickness and different densities. The density error rate generated by the scanner was between 1.54 and 1.35 percent, according to the researchers.

For the study, the researchers used the MicroDose mammography unit, a device sold by Philips Healthcare. The Dutch electronics giant bought the rights to MicroDose from its developer, the Swedish firm Sectra, in spring 2011, shortly after it was cleared by the Food and Drug Administration. (The MicroDose has been available in Europe, however, for nearly eight years.)

More research

The researchers said they hope to get a pilot study off the ground, involving real women and not just breast models. If the work holds up, in addition to helping doctors understand patients' risks, the technique could be used to monitor cancer treatments. For instance, Ding said the drug tamoxiflen can decrease density by 4.3 to 5.3 percent annually.

Although the device is commercially available now, Molloi said modifications would need to be done with the MicroDose's electronics, and that they would first have to be approved by the FDA.

"When those upgrades are done, every mammogram acquired could be used for its normal application and automatically would give you breast density," he said.