by

Lauren Dubinsky, Senior Reporter | November 06, 2017

First time DTI and fMRI

used in conjunction

Brain MR imaging techniques revealed that playing position and career duration contribute to white matter damage in former college and professional football players who suffered recurrent head impacts, according to a new study published in Radiology.

"Our findings may be useful in helping to develop prediction models for later-life neurodegenerative changes based on several factors, including playing position," Kevin Guskiewicz, research director for the Center for the Study of Retired Athletes at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, told HCB News.

Sixty-four former players between the ages of 52 and 65 were recruited for the study — half reported three or more prior concussions and the rest reported one or none. An equal amount of speed and non-speed playing positions were also recruited.

Ad Statistics

Times Displayed: 138115

Times Visited: 7975 MIT labs, experts in Multi-Vendor component level repair of: MRI Coils, RF amplifiers, Gradient Amplifiers Contrast Media Injectors. System repairs, sub-assembly repairs, component level repairs, refurbish/calibrate. info@mitlabsusa.com/+1 (305) 470-8013

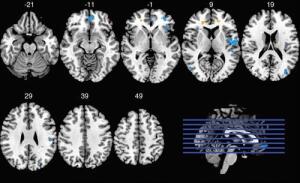

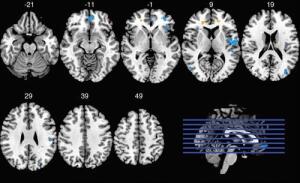

Guskiewicz and his team used diffusion tensor imaging and fMRI to evaluate 61 of the participants. The data from the other three participants was omitted because of excessive movement or inability to endure the exam.

The researchers used DTI to analyze the white matter's structural integrity and fMRI to assess the participants' brain function while performing a memory task.

This was the first time these two MR techniques were combined for concussion research. This allowed the team to visualize the relationship between structure and function, which are both affected by concussions.

The study results demonstrated a significant interaction between career duration and concussion history. The former college players with three or more concussions had lower integrity in a large portion of white matter, compared to those with one or no concussion.

However, the results were much different for the former professional players. The team noted that those with longer careers who have sustained recurrent concussions and are cognitively normal in their late 50s might not reflect the highly-exposed former professional football player population as a whole.

But they added that the results could also suggest that a longer career may not necessarily be worse than a shorter career in terms of white matter integrity.

"We were not surprised that longer football exposure was not associated with worse outcomes on clinical measures and neuroimaging findings," said Guskiewicz. "Previous research has suggested that a high volume of concussions (not subconcussive impacts) is more likely to be associated with poor outcomes."

The data also found that non-speed players with a history of recurrent concussion had less integrity in the frontal white matter and a lower amount of activation during the fMRI exam than those with one concussion or less. Alternatively, that was not the case for the speed players.

That suggests that there might be notable difference in injury mechanisms between speed and non-speed players. The magnitude, location and frequency of concussions differ based on position.

The team concluded that the playing position may change the effects concussions have on the brain. They recommend the use of position-specific helmets.

They cautioned that more work is required to better understand these findings as well as determine the underlying mechanisms regarding how subconcussive and concussive impacts affect brain health later in life.