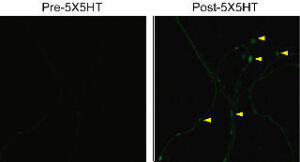

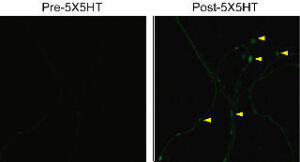

A robust increase in green fluorescence

of dendra reporter protein

represents local translation at synapse

during long-term synaptic plasticity

induced by 5X5HT

Courtesy: UCLA

UCLA and McGill University researchers have, for the first time "photographed" a memory in the making.

The study clarifies one of the ways in which connections in the brain between nerve cells, called synapses, can be changed with experience. The way nerve cells change while engaged in learning activities is called "synaptic plasticity" by scientists, and is the foundation for how we learn and remember.

As we learn, memories are stored as changes in the synaptic connections between nerve cells in our brain. Long-lasting changes in synaptic connections are required for long-term memories, and the persistence of these changes requires new gene expression via the synthesis of new proteins.

Ad Statistics

Times Displayed: 44187

Times Visited: 1363 Keep biomedical devices ready to go, so care teams can be ready to care for patients. GE HealthCare’s ReadySee™ helps overcome frustrations due to lack of network and device visibility, manual troubleshooting, and downtime.

This is the first study to use fluorescent imaging to visualize the synaptic plasticity and protein synthesis that occurs as we learn.

Understanding synaptic plasticity is critical to understanding diseases in which learning behaviors are impaired, researchers say. Such diseases include mental retardation, Alzheimer's disease, as well as anxiety, depression and a host of other mood disorders.

The research appears in the June 19 edition of the journal Science.

Sea Slug Aplysia Californica

In order to "see" the synaptic changes in the brain, researchers used sensory and motor neurons from the sea slug Aplysia Californica, which can form connections in culture dishes.

The neurons were stimulated with serotonin, which strengthens the synapses, and allows scientists to detect new protein synthesis--the making of a memory--using a "translational reporter," a fluorescent protein that can easily be tracked.

The studies revealed an exquisite level of control over the specificity of regulation of new protein synthesis, scientists say.

"While this was not really surprising to us given the complexity of information processing in the brain," said Kelsey Martin, associate professor of psychiatry and biological chemistry at UCLA and one of the study's authors, "visualizing the process of protein synthesis at individual synapses, and beginning to discern the elegance of its regulation, leaves us, as biologists, with a wonderful sense of awe."