From the May 2014 issue of HealthCare Business News magazine

Once an infected mosquito transfers malaria to a human body, the parasites multiply in the liver and attack the red blood cells. If left untreated, the infection can disrupt the blood supply to vital organs, resulting in fatal complications.

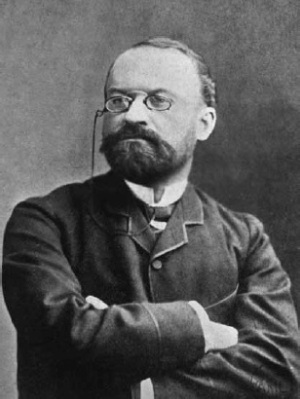

The world can thank a French military doctor named Charles Laveran for discovering the parasite that causes human malaria. Although he received a Nobel Prize for Medicine and Physiology for this discovery and other parasitological work, it took a while for the scientific community to accept his findings.

Charles Laveran was born in Paris on June 18, 1845. After obtaining his medical degree, he served as an ambulance officer during the Franco-German War. Then, he worked as a surgeon in various hospitals, taking a special interest in studying the infectious diseases of soldiers. At the age of 29, he was named Chair of Military Diseases and Epidemics at the École de Val-de-Grâce, a prestigious post previously held by his father. Although Laveran enjoyed his duties, the position did not leave him much time for research.

Ad Statistics

Times Displayed: 44472

Times Visited: 1374 Keep biomedical devices ready to go, so care teams can be ready to care for patients. GE HealthCare’s ReadySee™ helps overcome frustrations due to lack of network and device visibility, manual troubleshooting, and downtime.

Laveran welcomed the opportunity to dive back into research work in 1878, when he was sent to Algeria. Upon arrival, he found military hospitals full of soldiers who suffered from malaria. Laveran performed numerous autopsies on those who succumbed to the infection, only to find a strange black pigment on the internal organs. He then decided to inspect the fresh blood of malaria patients by taking blood specimens from infected soldiers.

On November 6, 1880, while looking at a droplet of blood on a glass slide through a microscope, Laveran noticed something unusual — a crescent-shaped object moving in a red blood cell. He watched in amazement as the object, which turned out to be a small malarial body, vigorously moved around, shaking the entire blood cell. He was witnessing a phase in the life cycle of a malaria parasite. Instantly, Laveran realized that he just found the tiny, living parasite that causes malaria. “I had no further doubts as to the parasitic nature of the elements I had found,” he later wrote of that day.

That winter, Laveran sent a letter to the Academy of Medicine in Paris describing his discovery, but it would take some time for the scientific community to accept his hypothesis. At the time, bacteriology, the notion that most infectious diseases were caused by germs, left many unconvinced that the parasite Laveran identified did indeed cause malaria.

It took years for other researchers to independently confirm Laveran’s findings. In 1885, a prominent Italian neurophysiologist not only publicly accepted Laveran’s hypothesis but also offered ample evidence to corroborate his work. Gradually, scientists in other countries published similar research. Finally, in 1889, the Academy of Sciences awarded Laveran a prize for his discovery, giving him the credit he deserved. Laveran also studied numerous soil, water, and air samples, and was among the first to suggest that mosquitoes transmitted malaria.

Despite the recognitions and honors bestowed upon him by leading scientists, Laveran was disappointed. After many years of dedication to the military service, Laveran believed many military leaders were indifferent and unappreciative of his discoveries.

In, 1896 Laveran was asked to run a laboratory at the Pasteur Institute, where he played a major role in leading research on tropical diseases. In 1907 he used his Nobel Prize money to establish the Laboratory of Tropical Diseases at the Pasteur Institute. Laveran also took on the responsibilities of a Commander of the Legion of Honour in the military, a role that enabled him to set the standards of care for injured or ill soldiers.

In the days leading up to his death on May 18, 1922, a weakened Laveran continued to oversee research in the lab with the help of an assistant. By the time of his death, he had published about 600 scientific works on the subject of parasites.